| Surrender Site at Citronelle General Richard Taylor surrendered the last major Confederate army east of the Mississippi River at Citronelle, Alabama. |

Citronelle, Alabama

The surrender site is now a small

park area facing Center Street.

The war east of the Mississippi

ended here, not at Appomattox.

The surrender site is now a small

park area facing Center Street.

The war east of the Mississippi

ended here, not at Appomattox.

War east of the Mississippi

Lt. Gen. RIchard Taylor (CSA), son

of President Zachary Taylor, gave

up the fight at this site on May 4,

1865.

Lt. Gen. RIchard Taylor (CSA), son

of President Zachary Taylor, gave

up the fight at this site on May 4,

1865.

SURRENDER AT CITRONELLE

Citronelle, Alabama

Citronelle, Alabama

End of the War in the East

| Copyright 2014 & 2017 by Dale Cox All rights reserved. Last Updated: May 4, 2017 |

Custom Search

Civil War Sites in Alabama

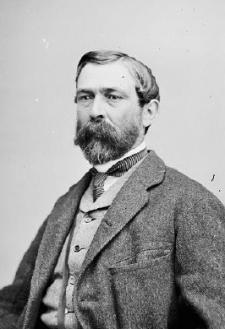

Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, CSA

General Taylor was the hard-

fighting Confederate leader who

drove back the Union's Red River

Campaign.

General Taylor was the hard-

fighting Confederate leader who

drove back the Union's Red River

Campaign.

The last major Confederate army

east of the Mississippi surrendered

beneath an oak tree north of Mobile,

Alabama, on May 4, 1865.

Confederate Lt. Gen Richard Taylor

came to agreement with Union Major

General E.R.S. Canby by the railroad

tracks in Citronelle, Alabama. His

surrender ended significant combat

east of the Mississipi. The last shots

were still to be fired, but the war was

over in the East.

east of the Mississippi surrendered

beneath an oak tree north of Mobile,

Alabama, on May 4, 1865.

Confederate Lt. Gen Richard Taylor

came to agreement with Union Major

General E.R.S. Canby by the railroad

tracks in Citronelle, Alabama. His

surrender ended significant combat

east of the Mississipi. The last shots

were still to be fired, but the war was

over in the East.

Battle of Ebenezer Church

Battle of Mobile Bay

Battle of Spanish Fort

Battle of Selma

Confederate Memorial Park

First Capitol of the Confederacy

Fort Gaines Historic Site

Fort Morgan State Historic Site

Battle of Mobile Bay

Battle of Spanish Fort

Battle of Selma

Confederate Memorial Park

First Capitol of the Confederacy

Fort Gaines Historic Site

Fort Morgan State Historic Site

The site is commemorated today at a small park. Exhibits on the surrender can

be seen at the nearby Citronelle Historical Museum.

Even after the surrender of General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia at

Appomatox Court House, fighting continued as three major campaigns went

forward. In North Carolina, General Joseph E. Johnston had yet to surrender to

Sherman at Bennett Place. In Alabama and Georgia, Southern troops resisted

Wilson's Raid of 1865. On the Gulf Coast, the fighting of the Mobile Campaign

continued to rage.

The key actions of the latter campaign took place at Spanish Fort on April 8 and

Fort Blakeley on April 9. With these important East Shore defenses in Union

hands, Mobile was evacuated by its Confederate defenders and fell to Union

troops on April 12, 1865.

Over the weeks that followed, the armies of Generals Taylor and Canby

continued to eye each other as each commander absorbed news of disasters

coming in from other fronts. Taylor was the hard-fighting son of U.S. President

Zachary Taylor while Canby was a career army officer. Each man was prepared

to do his duty.

Taylor knew the Confederacy was about to fall and was honest with his men

about the situation:

It was but right to tell these gallant, faithful men the whole truth concerning our

situation. The surrender of Lee left us little hope of success; but while Johnston

remained in arms we must be prepared to fight our way to him. Again, the

President and civil authorities of our Government were on their way to the south,

and might need our protection. Granting the cause for which we had fought to be

lost, we owed it to our own manhood, to the memory of the dead, and to the

honor of our arms, to remain steadfast to the last. This was received, not with

noisy cheers, but solemn murmurs of approval... - Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, CSA

(Destruction and Reconstruction, p. 222).

Inspired by Taylor and his subordinates - Generals Nathan Bedford Forrest and

D.H. Maury - the men of the Confederate army remained steadfast. Then came

news from North Carolina that Generals Johnston and Sherman had agreed to a

truce.

Requested by those generals to negotiate a similar ceasefire, Taylor and Canby

agreed to meet at the Magee Farm in the community of Kushla north of Mobile.

There on April 29 they agreed to a truce while they awaited the decisions of their

governments on the terms agreed to by Sherman and Johnston.

Two days later they learned that the U.S. government had disavowed the

honorable terms offered Johnston by Sherman. Canby regretfully notified Taylor

that their ceasefire would end in 48 hours.

The fate of his men now rested on Taylor's shoulders. Having learned of the

capture of President Jefferson Davis in Georgia and of Johnston's final

surrender to Sherman at Bennett Place, he decided to bring the war east of the

Mississippi to an end:

...Bank stocks, bonds, all personal property, all accumulated wealth, had

disappeared. Thousands of houses, farm-buildings, work-animals, flocks and

herds, had been wantonly burned, killed, or carried off. The land was filled with

widows and orphans crying for aid, which the universal destitution prevented

them from receiving. - Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, CSA (Destruction and

Reconstruction p. 236).

The two generals met at Citronelle in Mobile County on May 4, 1865. The town

takes its name from the citronella plant and was founded in 1811. It was selected

as the meeting point due to its location on the railroad between Canby's

headquarters at Mobile and Taylor's in Meridian, Mississippi.

General Taylor wrote after the war that the terms offered by General Canby

were "consistent with the honor of our arms." Men with horses could keep them,

officers would retain their sidearms, the Confederate soldiers would be paroled

and Taylor would retain control of railways and river steamers to help them get

home.

The agreement was reduced to writing and Taylor signed it using a pen

fashioned from a steel point attached to a twig and dipped in ink. The

Confederacy was so destitute that real pens could no longer be found.

The surrender at Citronelle brought the War Between the States (or Civil War)

east of the Mississippi to its end. The Confederates were paroled over the

coming weeks and General Canby helped his former enemy reach his home in

New Orleans.

Acting partially on advice from Taylor, General Kirby Smith laid down his arms at

Galveston, Texas on June 2, 1865. His surrender ended the possibility of a

continuation of the war west of the Mississippi, although it was not until June 23

that Brigadier General Stand Watie surrendered at Doaksville in what is now

Oklahoma. The last Southern general to lay down his arms, Watie was the only

American Indian to achieve such rank in either army.

His military career at an end, General Taylor wrote his memoirs after the war and

was active in Democrat Party politics. He died in New York on April 12, 1879, and

was buried in Metairie, Louisiana. General Nathan Bedford Forrest said of him,

"He's the biggest man in the lot."

General Canby remained in the U.S. Army after the war and was killed while

trying to reach a peace agreement with the Modoc Indians of California. He was

shot and his throat was cut by Modoc chiefs on April 11, 1873. His body was

returned home for burial in Indianapolis, Indiana.

The site where Lieutenant General Richard Taylor surrendered to Major General

E.R.S. Canby is now preserved as a small park in Citronelle, Alabama. Located

near the south end of Centre Street, it offers no facilities but features markers

and picnic tables. Displays on the surrender can be seen at the nearby

Citronelle Historical Museum.

The park is open to the public during daylight hours.

be seen at the nearby Citronelle Historical Museum.

Even after the surrender of General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia at

Appomatox Court House, fighting continued as three major campaigns went

forward. In North Carolina, General Joseph E. Johnston had yet to surrender to

Sherman at Bennett Place. In Alabama and Georgia, Southern troops resisted

Wilson's Raid of 1865. On the Gulf Coast, the fighting of the Mobile Campaign

continued to rage.

The key actions of the latter campaign took place at Spanish Fort on April 8 and

Fort Blakeley on April 9. With these important East Shore defenses in Union

hands, Mobile was evacuated by its Confederate defenders and fell to Union

troops on April 12, 1865.

Over the weeks that followed, the armies of Generals Taylor and Canby

continued to eye each other as each commander absorbed news of disasters

coming in from other fronts. Taylor was the hard-fighting son of U.S. President

Zachary Taylor while Canby was a career army officer. Each man was prepared

to do his duty.

Taylor knew the Confederacy was about to fall and was honest with his men

about the situation:

It was but right to tell these gallant, faithful men the whole truth concerning our

situation. The surrender of Lee left us little hope of success; but while Johnston

remained in arms we must be prepared to fight our way to him. Again, the

President and civil authorities of our Government were on their way to the south,

and might need our protection. Granting the cause for which we had fought to be

lost, we owed it to our own manhood, to the memory of the dead, and to the

honor of our arms, to remain steadfast to the last. This was received, not with

noisy cheers, but solemn murmurs of approval... - Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, CSA

(Destruction and Reconstruction, p. 222).

Inspired by Taylor and his subordinates - Generals Nathan Bedford Forrest and

D.H. Maury - the men of the Confederate army remained steadfast. Then came

news from North Carolina that Generals Johnston and Sherman had agreed to a

truce.

Requested by those generals to negotiate a similar ceasefire, Taylor and Canby

agreed to meet at the Magee Farm in the community of Kushla north of Mobile.

There on April 29 they agreed to a truce while they awaited the decisions of their

governments on the terms agreed to by Sherman and Johnston.

Two days later they learned that the U.S. government had disavowed the

honorable terms offered Johnston by Sherman. Canby regretfully notified Taylor

that their ceasefire would end in 48 hours.

The fate of his men now rested on Taylor's shoulders. Having learned of the

capture of President Jefferson Davis in Georgia and of Johnston's final

surrender to Sherman at Bennett Place, he decided to bring the war east of the

Mississippi to an end:

...Bank stocks, bonds, all personal property, all accumulated wealth, had

disappeared. Thousands of houses, farm-buildings, work-animals, flocks and

herds, had been wantonly burned, killed, or carried off. The land was filled with

widows and orphans crying for aid, which the universal destitution prevented

them from receiving. - Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, CSA (Destruction and

Reconstruction p. 236).

The two generals met at Citronelle in Mobile County on May 4, 1865. The town

takes its name from the citronella plant and was founded in 1811. It was selected

as the meeting point due to its location on the railroad between Canby's

headquarters at Mobile and Taylor's in Meridian, Mississippi.

General Taylor wrote after the war that the terms offered by General Canby

were "consistent with the honor of our arms." Men with horses could keep them,

officers would retain their sidearms, the Confederate soldiers would be paroled

and Taylor would retain control of railways and river steamers to help them get

home.

The agreement was reduced to writing and Taylor signed it using a pen

fashioned from a steel point attached to a twig and dipped in ink. The

Confederacy was so destitute that real pens could no longer be found.

The surrender at Citronelle brought the War Between the States (or Civil War)

east of the Mississippi to its end. The Confederates were paroled over the

coming weeks and General Canby helped his former enemy reach his home in

New Orleans.

Acting partially on advice from Taylor, General Kirby Smith laid down his arms at

Galveston, Texas on June 2, 1865. His surrender ended the possibility of a

continuation of the war west of the Mississippi, although it was not until June 23

that Brigadier General Stand Watie surrendered at Doaksville in what is now

Oklahoma. The last Southern general to lay down his arms, Watie was the only

American Indian to achieve such rank in either army.

His military career at an end, General Taylor wrote his memoirs after the war and

was active in Democrat Party politics. He died in New York on April 12, 1879, and

was buried in Metairie, Louisiana. General Nathan Bedford Forrest said of him,

"He's the biggest man in the lot."

General Canby remained in the U.S. Army after the war and was killed while

trying to reach a peace agreement with the Modoc Indians of California. He was

shot and his throat was cut by Modoc chiefs on April 11, 1873. His body was

returned home for burial in Indianapolis, Indiana.

The site where Lieutenant General Richard Taylor surrendered to Major General

E.R.S. Canby is now preserved as a small park in Citronelle, Alabama. Located

near the south end of Centre Street, it offers no facilities but features markers

and picnic tables. Displays on the surrender can be seen at the nearby

Citronelle Historical Museum.

The park is open to the public during daylight hours.

Maj. Gen. E.R.S. Canby, USA

General Canby was killed at a

peace conference by Modoc

Indian warriors seven years after

he negotiated Taylor's surrender

at Citronelle.

General Canby was killed at a

peace conference by Modoc

Indian warriors seven years after

he negotiated Taylor's surrender

at Citronelle.

The Battle of Mobile Bay

The Mobile Campaign

The Battle of Spanish Fort

The Battle of Fort Blakeley

The Magee Farm Truce

Historic Sites in Mobile, Alabama

Historic Sites in Alabama

Battlefields & Forts of the South

Explore other Southern Historic Sites

The Mobile Campaign

The Battle of Spanish Fort

The Battle of Fort Blakeley

The Magee Farm Truce

Historic Sites in Mobile, Alabama

Historic Sites in Alabama

Battlefields & Forts of the South

Explore other Southern Historic Sites

Historic Railroad Trail

The railroad by which the two

generals arrived at Citronelle is

now a walking and biking path. It

passes by the historic surrender

site.

The railroad by which the two

generals arrived at Citronelle is

now a walking and biking path. It

passes by the historic surrender

site.

The Mobile Campaign

Taylor's surrender came after a

bitter and hard fought campaign

in which Union forces captured

Spanish Fort and Fort Blakeley

(above) before marching into

Mobile, Alabama.

Taylor's surrender came after a

bitter and hard fought campaign

in which Union forces captured

Spanish Fort and Fort Blakeley

(above) before marching into

Mobile, Alabama.